Guide To Understanding Civil War Photos and FAQ

First off, there are two basic kinds of CW photos. The first type is the millions of individual portraits of loved ones, usually in the form of tintypes or other little one-of-a-kind, Polaroid-like photographs on metal. These were photographic keepsakes and were highly cherished, but had no impact on public perception. The documentary photographs, or scenic photos, did have some impact, for sure, although it was more limited than the kind of impact that images had, say, during the Vietnam war.

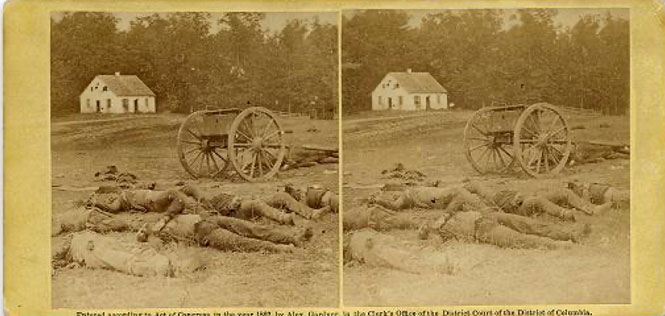

The first extensive photography of the dead on the battlefield, taken at Antietam, caused a sensation when the images were put on display at Brady’s New York gallery about a month after the battle. Long lines formed to see them. they were also reproduced as woodcut engravings in the biggest weekly illustrated new magazine of the day, Harper’s Weekly (although they could not be reproduced as actual photographs in newspapers – that would come around 1880). The New York Times reported on Oct. 18, 1862 of the photograph exhibition: “If Brady has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along our streets, he has done something very like it.”

They had to create their “film” on the spot, and develop it on the spot. The “film” was a glass plate negative — either 7×9 inches or for stereo, 4 by 10 inches. The glass looks like regular window glass, but the photographers had to coat it with light-sensitive emulsion right on the spot and expose the picture while it was wet and then immediately develop the negative. I refer you to my new book, The Blue and Gray in Black and White, for this passage:

“For the men behind the lenses, the great adventure was fraught with hardship and danger, frustration and doubt. They were bedeviled by the same flies and gnawed by the same mosquitoes that plagued the soldiers in the trenches. They were hardened by same soaking rains and the same baking sun that tormented the long lines of men trudging beside their wagons. In Charleston in 1863 and 1864, George S. Cook not only had to wage a daily battle against Confederate inflation, he had to endure the daily bombardment of the city.”

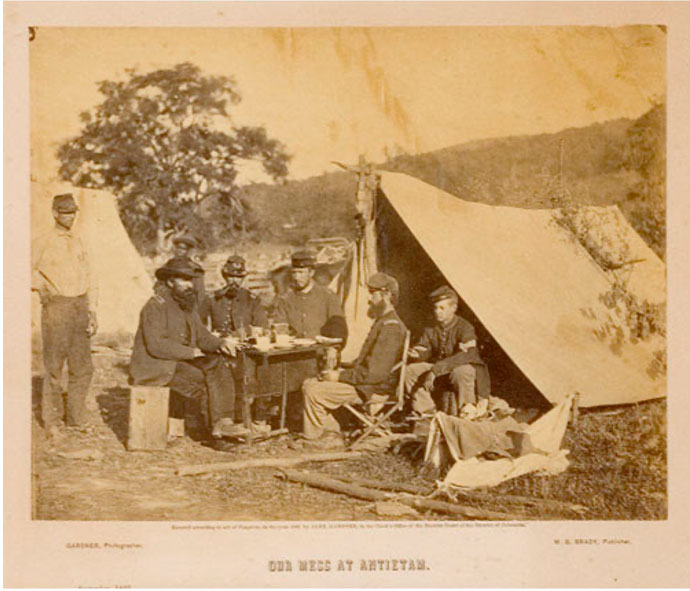

Most of the documentary photographs were taken by a small handful of the biggest photographers in the country, generally based in the biggest cities. They made prints of their photos and mounted them on boards and sold them that way. My estimate is that about 70 percent of the documentary photos of the war (there were probably 7,000 to 10,000 taken) were taken in 3-D, to be seen in a stereo viewer. These ended up being side-by-side photos, each 3×3 inches, mounted on a slightly larger card. They were stereo views. This was the ‘video’ of Civil War America. We’ve got examples on our website. They did have a fairly wide audience in the middle and upper classes. Stereo views were the first form of American home entertainment. See examples below — first a large plate 7×9 inch mounted image (shown smaller than actual size) , then a stereo view of Antietam and the Dunker Church. Both photos were taken by Alexander Gardner, the manager of Brady’s Washington gallery, and published by Brady, as the mount on the large photo says.

They were motivated primarily by making money, but also by the idea that they were recording history and being part of the great adventure.

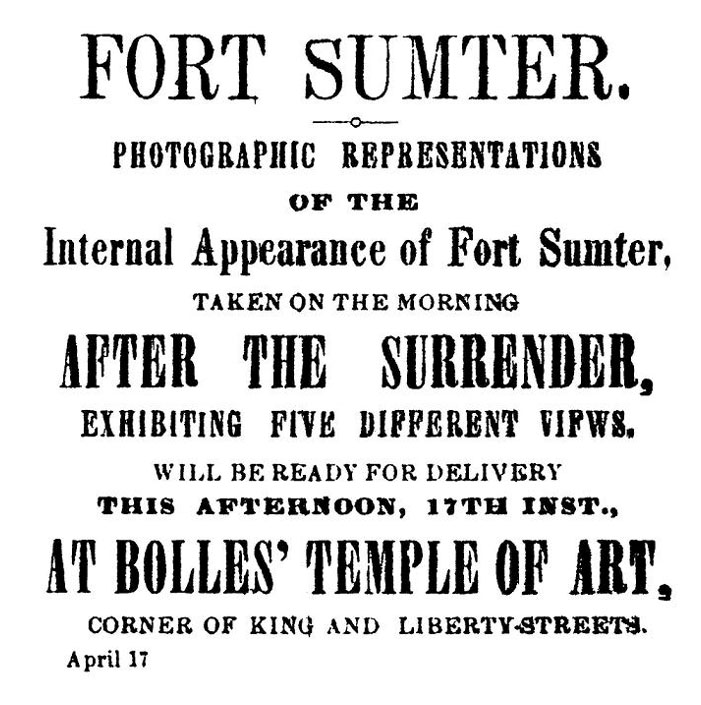

Generally there would be small news articles reporting that photographers had taken certain pictures and they were available at so-and-so’s gallery. When George S. Cook took remarkable photos of Union (enemy) ironclads in action in Charleston Harbor, it was reported in at least two papers in the south and one in the north. On some occasions, photographers advertised their photos, such as this ad on the following page, which appeared in the Charleston, S.C. Courier a few days after Fort Sumter fell in 1861.

There is only one recorded instance of an actual body being moved to enhance a picture, and that’s the shot of the “sharpshooter” (actually an infantryman) in the so-called sharpshooter’s nest at Gettysburg. As mentioned earlier, in a few other images of the dead, props have been laid in the photos, such as a rifle or a canteen, for added effect.

There were well over 6,000 photographers in the United States during the Civil War, but only a very few – a handful – did anything other than to shoot portraits of people: small town photographers working in the confines of their studio.

The Library of Congress owns the core collections of the most active commercial documentary photographers, namely Alexander Gardner and his associates, Mathew B. Brady and his associates, and the E & H.T. Anthony & Co., (the Kodak of its day), which issued 1,100 stereo views of Civil War photos at the end of the war.

The documentary photos consist of several basic types — large plate photos on 7×9 inch glass plate negatives, and stereoscopic photos, which consisted of two side-by-side images on a 4 x10 inch glass plate, which was often cut and trimmed to two 3×3 squares.

The handheld stereoscopic viewer (think View Master) was the video of Civil War America. This was the photographic viewing experience — where a person could disappear under the hood of the view and into the scene — the closest thing to TV back then and the first form of mass marketed American home entertainment.

The Library of Congress collections include more than 700 large plates by Gardner, as well as almost 1,000 stereo views or half stereos, along with the Anthony War for the Union stereo view series of more than 1,000 negatives.

Yes, but they did not consider themselves only photojournalists. Gardner, Brady and the others in this small group who mass marketed documentary images saw themselves as artists – akin to painters – as much as anything else. It was just that their art was painted by the sun. But they clearly saw themselves as providing the vision for the art — in other words, what to aim the camera at.

Gardner served as Brady’s Washington gallery manager until around the end of 1862, or after he took the famous photos at Antietam. By May 1863, he was on his own and operating his own gallery in Washington.

Gardner was more of a photojournalist than Brady. In some of Gardner’s shots of the dead from Gettysburg and Spotsylvania you can see that some props have been added, such as a musket, or canteen, or other objects. This was, of course, to enhance the content of the photo.

Brady was more of the artist. He arrived too late at Gettysburg to shoot bodies, like Gardner did, but tried to set up at least one, placing an assistant on the ground in one Gettysburg shot with an ID as “wounded soldier.” But Brady was much more likely to use himself or an assistant and place them in the picture for a better artistic effect.